Aries, goat or ram.

Machzor, London 1772.

|

|

Aries, goat or ram. Machzor, London 1772. |

Pesach, Passover 1. which is linked to the sacrifice of a young lamb or kid. 2. Pesach is the spring festival when we remember the exodus from Egypt. The name Pesach is usually taken as coming from the verse: It is the sacrifice of the Lord�s Passover, who passed over the houses of the people of Israel in Egypt, when he struck the Egyptians, and saved our houses.3. There the Hebrew word for passed over is pasach. The English word Passover comes from the same verse. However the name may be even older than this for

Pesach, Passover 1. which is linked to the sacrifice of a young lamb or kid. 2. Pesach is the spring festival when we remember the exodus from Egypt. The name Pesach is usually taken as coming from the verse: It is the sacrifice of the Lord�s Passover, who passed over the houses of the people of Israel in Egypt, when he struck the Egyptians, and saved our houses.3. There the Hebrew word for passed over is pasach. The English word Passover comes from the same verse. However the name may be even older than this for  pasach also means to dance or skip and may refer to the skipping of young lambs. And Pesach may have been an ancient festival giving thanks for the birth of young lambs and kids which took place at this season.

pasach also means to dance or skip and may refer to the skipping of young lambs. And Pesach may have been an ancient festival giving thanks for the birth of young lambs and kids which took place at this season.

Chag Ha-Matsot the Festival of Unleavened Bread.4. This is because the festival is linked with the barley harvest. The two main symbols, the lamb bone and the matsah, go back to the two main types of farming when the Israelites were either nomadic shepherds or settled growers of crops. In each case the festival was one of thanksgiving for God's gifts in nature at spring time.

Chag Ha-Matsot the Festival of Unleavened Bread.4. This is because the festival is linked with the barley harvest. The two main symbols, the lamb bone and the matsah, go back to the two main types of farming when the Israelites were either nomadic shepherds or settled growers of crops. In each case the festival was one of thanksgiving for God's gifts in nature at spring time.

Z'man Cherutenu, the Season of our Freedom. The phrase dates from Rabbinic times and is used in our liturgy.5. This name emphasises the main theme of the festival.

Z'man Cherutenu, the Season of our Freedom. The phrase dates from Rabbinic times and is used in our liturgy.5. This name emphasises the main theme of the festival.

(1.) Exodus 12, 11, etc. (2.)Exodus 12, 5. (3.) Ex. 12, 27. (4.) Ex. 23, 15, Lev. 23, 6, etc. (5.) eg. The Kiddush.

The two main symbols of Passover, the Paschal lamb (or kid) and the Matsah are both agricultural. It has therefore been suggested that they do not stem from either Egyptian slavery or the wilderness years. They were thanksgiving for newly harvested grain and new-born lambs of springtime, which would have been more appropriate to the periods of settlement in Canaan. When Moses said to Pharaoh Let My people go that they may serve Me in the wilderness,6. it implied that they wished to observe some old-established festival sacrifice. There are some traditional sources which claim that Abraham, Isaac and Jacob observed Passover 7. long before the exodus. These latter sources are Midrashic rather than historical and, being of a late date, are not valid proof.

Passover was observed during the period of Joshua but later observance was sometimes very lax. The laws had to be restated and the observance had to be re-enforced during the reforms of Josiah 8. and in the time of Hezekiah. 9.

The Paschal sacrifice was a popular observance during the period of the second Temple. Josephus records that one year in the first century CE, about 2,702,000 Jews were reported to have carried out the sacrifice.10. However this figure seems to be highly exaggerated. After the fall of the second Temple and during the times of Mishnah and Talmud, the observance of the festival was given a new shape. Synagogue services and the observance of the seder in the home became established. At the same time, the Rabbis defined the Passover laws more and more strictly so as to prevent Jews from transgressing by accident. At the present day some Jews find the food laws so burdensome that they choose to spend Passover at a Jewish Hotel, where all the worry is taken from them. But this means that they loose much of the benefit of observing it among the family at home.

(6.) Exodus 7, 16; 8, 23; 8, 16, etc. (7.) Targum Jonathan to Gen. 14, 13. Deut. Rabba 1, 25. and Targum Jonathan to Gen. 27, 9. (8.) 2 Kings 23, 22. (9.) 2 Chron. 30, 1- 20. (10.) Josephus: War, 6, 9, #3.

|

|

|

And this day shall be to you for a memorial; and you shall keep it a feast to the Lord throughout your generations; you shall keep it a feast by an ordinance forever. Seven days shall you eat unleavened bread; the first day you shall put away leaven out of your houses; for whoever eats leavened bread from the first day until the seventh day, that soul shall be cut off from Israel. And in the first day there shall be a holy convocation, and in the seventh day there shall be a holy convocation to you; no kind of work shall be done in them, save that which every man must eat, only that may be done by you.. And you shall observe the Feast of Unleavened Bread; for in this same day have I brought your hosts out of the land of Egypt; therefore shall you observe this day in your generations by an ordinance forever. In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at evening, you shall eat unleavened bread, until the twenty first day of the month at evening.11.

From this we learn:

Those Orthodox Jews who live outside Israel observe the festival for an extra day making eight days. They keep the first two days and the last two days as full festival days. (For the explanation, see SECOND DAYS OF FESTIVALS.)

There are also instructions for the first Passover where the Israelites killed lambs and daubed the blood on the door posts of their houses and then roasted and ate the lambs, while they were dressed and ready for the impending journey.12. The observance of that first Passover was different from the later ones. It was the only one with the daubing of blood and most Jews do not eat in haste and with their loins girded.13. Rather than eating in haste, the Haggadah (the prayer book for the 1st night of Passover) says that we should linger over the telling of the story of the Exodus.

(11.) Exodus 12, 14 -18. (12.) Exodus 12, 2 - 11. (13.) Exodus 12, 11.

|

|

|

The Rabbis were concerned that Matsot should be truly unleavened. They knew that when one bakes leavened bread, the custom was to mix in yeast, knead the flour and water into dough then leave it in a warm place for a long time, in order that the yeast should work and bread rise. For matsot these requirements were deliberately changed. One was required to keep the dough cool and to bake it quickly before it had time to rise. In order to prevent leavening they forbade water from a well as this was thought to be warm at that time of year and insisted that matsot should be made from water kept in a cool place over night. (see also HOLES IN MATSAH.)

|

|

before handling dough, Venice, 1609. |

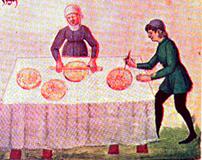

They defined the maximum time allowed from the adding of water to the flour until the completion of the baking to be 18 minutes. They said that this was the time taken to walk 2000 cubits (roughly a kilometre) 14.To achieve this time both the preparation and the baking had to be speeded up. They used very hot ovens for the baking. And the Jewish communities organised working parties to form teams to work together. The picture from Mantua shows what looks like an efficient production line working, long before the factories of the industrial revolution.

The ovens were obviously of different designs. The Mishnah describes Passover ovens that were moved inside when there was a risk of rain 15. An oven found at the Ostia Synagogue (c. 3rd Cent CE) and those shown on this web page are definitely permanent fixtures.

(14.) Pes. 46a. (15.) Ta'anit 3, 3.

|  |

|

Note spike making single holes. |

Note combs on table. |

Holes are put into matsah to let the gases escape and to stop it leavening and rising. Originally these were put in one at a time (see Rothschild Manuscript, Italy 1470.) This was a very slow process and was soon speeded up by the use of multi-toothed combs. (see Utrecht 1663) Some examples of these survive in museums.

In the 19th century when machines were invented for making matsot, there was a heated controversy as to whether such matsot really filled the requirements, as scraps of dough might stick to machine parts and "contaminate" with leaven. 16. Another result of machinery was to change the shape of matsot. Hand-made matsot were always round being the natural shape of rolling out a ball of dough. Machine matsot are square being made by chopping up a continuous ribbon of dough, and the holes are in very straight lines as can be seen from the background to this website.

(16.) Freehof: The Responsa Literature pp. 181ff.

The verse the first day you shall put away leaven (S'or) out of your houses; for whoever eats leavened bread (Chamets) from the first day until the seventh day, that soul shall be cut off from Israel. 17. is taken to refer to two different things.  Chamets is the dough that has fermented or products cooked with it. While

Chamets is the dough that has fermented or products cooked with it. While  S'or is the substance which causes fermentation. It is generally accepted that flour made from wheat, barley, spelt, rye and oats is liable to be affected by leavening. But Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews differ on other substances. Ashkenazi Jews regard rice as liable to ferment and they also forbid the eating of pulses or foods like them. They therefore do not eat beans, peas, maize and peanuts during Pesach. The Sephardim permit all these foods. These differences of opinion date back to the Talmud. 18. The Ashkenazim gradually introduced these extra prohibitions after the end of the Talmudic period. Some were forbidden because flour made from some of these might have given the impression that Jews were eating forbidden food. 19.

S'or is the substance which causes fermentation. It is generally accepted that flour made from wheat, barley, spelt, rye and oats is liable to be affected by leavening. But Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews differ on other substances. Ashkenazi Jews regard rice as liable to ferment and they also forbid the eating of pulses or foods like them. They therefore do not eat beans, peas, maize and peanuts during Pesach. The Sephardim permit all these foods. These differences of opinion date back to the Talmud. 18. The Ashkenazim gradually introduced these extra prohibitions after the end of the Talmudic period. Some were forbidden because flour made from some of these might have given the impression that Jews were eating forbidden food. 19.

(17.) Exodus 12, 15. (18.) Pes. 35a. (19.) Enc. Judaica vol. 7, p. 1236.

|

|

Prague, 1526. |

Because the Torah says you shall put away leaven out of your houses,20. it became an annual event to spring-clean the house before Passover and then to search ceremonially for leavening in all the rooms. The ceremony known as  B'dikat Chamets (Searching for Leavened Food) requires a blessing to be said first, which states that one is fulfilling the mitsvah of clearing out chamets. The father of the family goes round with a candle to provide light into dark corners and a feather to brush up any crumbs found. All chamets found is carefully bundled up and taken outside and burnt. Because it is thought wrong to say a blessing in vain, 21. the mother of the house deliberately places a piece of chamets in each room.

B'dikat Chamets (Searching for Leavened Food) requires a blessing to be said first, which states that one is fulfilling the mitsvah of clearing out chamets. The father of the family goes round with a candle to provide light into dark corners and a feather to brush up any crumbs found. All chamets found is carefully bundled up and taken outside and burnt. Because it is thought wrong to say a blessing in vain, 21. the mother of the house deliberately places a piece of chamets in each room.

In case someone had missed a crumb somewhere, after completing the search, in order to clear himself from blame he would then say a legal formula which declared that any chamets still in his possession is annulled and considered masterless, like the dust of the earth.22. Apart from being sexist role playing, one can not help wondering if this excessive attention to legal interpretation of a Biblical text is really the best way to celebrate a festival of freedom or whether it is not perilously close to becoming slavery to superstition.

(20.) Exodus 12, 15. (21.) Isserles, S.A. Orach Chayim 431, 2. (22.) Art Scroll Haggadah p. xliv.

The custom of selling chamets before Passover begins has developed in four stages. In the Encyclopoedia Judaica 23. Rabbi H. Rabinowicz lists these as:

(23.) vol 7, p. 1238. (24.) Pes. 13a. (25.) S.A. Orach Chayim 448, 3. But the custom dates back well before this.(26.) Bayit Chadash, Orach Chayim 448.

|

|

them Kasher for Pesach Venice 1609. |

|

|

Pesach, Holland 1657. |

The Biblical command that there should be no leaven in the home was interpreted more and more strictly as time passed. Succeeding generations of Rabbis, following the tradition of putting a fence round the Torah 27. so that no one might transgress by accident, gradually introduced more and more restrictions. From early times the rule had been that although in the rest of the year if a drop of unsuitable food dropped into a pot by accident and if it was less than one sixtieth of the bulk then the resulting food was regarded as Kasher. However at Pesach even the slightest bit of leaven makes the whole dish unsuitable for eating. 28. This meant that great care had to be taken to see that not a scrap of leaven could enter the food preparation in the kitchen.

The fear that small particles of leavened food might be sticking to work surfaces, the oven or to pots, pans, dishes, plates or cutlery led to very detailed processes of cleansing before Passover.

(27.) Avot 1, 1. (28.) Ganzfried: K.S.A. 3, 117, #1.

|

|

Venice Haggadah, 1609. |

Some Jews are not satisfied with ordinary matsot, fearing that leavening might have taken place in the flour even before the making process begins. So a small amount of matsot are made from flour which has been carefully watched over from the time that the corn harvested right through the milling process to ensure that no damp has reached it. Matsot made from such flour are called MATSAH SH'MURAH.

These Jews believe that Matsah Sh'murah must be used for the THREE PIECES OF MATSAH placed specially on the Seder table,29. for they are used for fulfilling the mitsvah of eating Matsah on the eve of Passover. This is the only occasion when we are positively required to eat Matsah. For the remainder of Passover we are just commanded not to eat leavened bread. There are a few Jews who are particularly fussy who eat only Matsah Sh'murah and no other type. The risk of leavening taking place before the beginning of the mixing and baking process is minimal, but there has always been a holier-than-thou attitude among some Jews over food matters.

(29.) Art Scroll Haggadah, p. xxxviii.

Elderly members of my congregation told me of their recollections of Passover in the East End of London in the 1930s.

| FOR FULL ALPHABETICAL INDEX |